In the 5th century, Greek philosopher Democritus, first theorized that atoms are constantly moving. Today, we understand that these building blocks of matter are, in fact, in constant motion and that this activity produces energy.

In the 5th century, Greek philosopher Democritus, first theorized that atoms are constantly moving. Today, we understand that these building blocks of matter are, in fact, in constant motion and that this activity produces energy.

Scientifically, in the most remedial sense, we are made up of atoms therefore our matter is perpetual energy. And from science to spirituality alike, we know and have experienced that energy is contagious, cross-species.

The nature of our bodies have built in mechanisms to internally produce and absorb energy, as well as physical responses to expel energy that our bodies have absorbed and/or processed and no longer have use for or require. These responses, known as instinctive reflexes, are true for all human beings regardless of race, nationality, economic status, age, or any other variance of uniqueness.

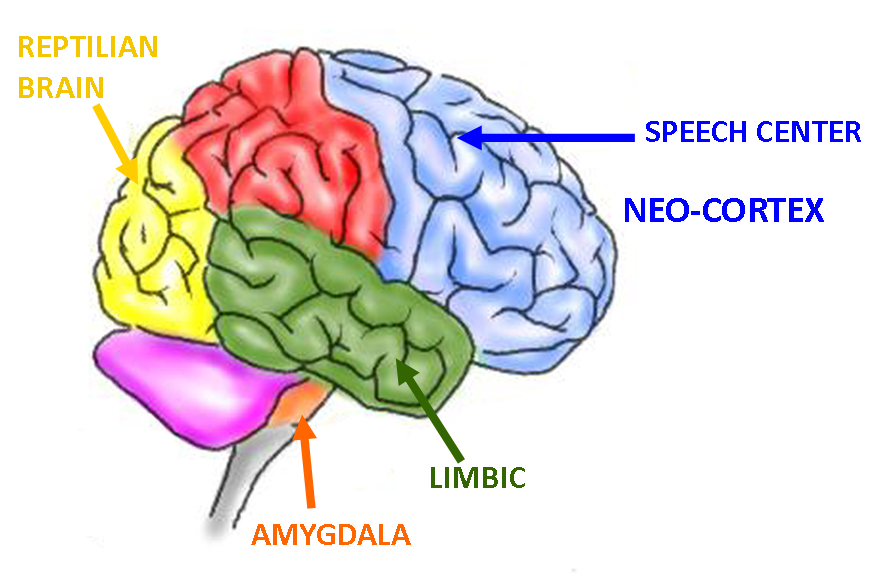

Like instinctive reflexes, each of us has a developed survival strategy, an automatic response to perceived or actual threats to our being or ego. Whether one’s survival strategy is flight, fight, freeze, or appease, the physiological and neurological results are the same- dilated pupils, goosebumps, sweating, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate and widen bronchial passages, and the takeover of the amygdala that simultaneously shuts down the neo-cortex, the part of our brain that controls higher functions like logic and reason.

While some science can be absolute and universally true for all human beings, the many variables and how society defines who we are through such things as privilege, race, ethnicity, “gender”, sexuality, economics, and environment, all add layers of complexity to understanding how these universal scientific truths shape and impact our bodies, our relationships, and our lives.

Let’s put all of this into context… Imagine you are walking down a busy street. You are in a spectacular mood as the sun is shining and the birds are singing. You’re on your merry way and, all of a sudden, someone bumps into you. Hard. And without breaking their stride, they bark something accusatory at you as you absorb the hit and have instantly been triggered into your survival strategy. Now, you are not so merry. Now, you may even be angered, upset, or even scared but regardless, there is an electric tension that has you alert and has dramatically shifted your mood. This transfigured energy is now yours with the potential of passing it along to someone else you have an intentional or unintentional interaction with either on the street or wherever you were heading.

Let’s put all of this into context… Imagine you are walking down a busy street. You are in a spectacular mood as the sun is shining and the birds are singing. You’re on your merry way and, all of a sudden, someone bumps into you. Hard. And without breaking their stride, they bark something accusatory at you as you absorb the hit and have instantly been triggered into your survival strategy. Now, you are not so merry. Now, you may even be angered, upset, or even scared but regardless, there is an electric tension that has you alert and has dramatically shifted your mood. This transfigured energy is now yours with the potential of passing it along to someone else you have an intentional or unintentional interaction with either on the street or wherever you were heading.

This is vomiting rage.

If we introduce social science into our understanding of energy and survival strategies, we can further analyze how deeply impactful the variables, that socially define us, can have in our lives. The more intersections of race, class, ethnicity, religious belief, sexuality, “gender” and other identities that we may choose, the greater oppression one likely will experience across the board.

While oppression is largely understood as being external systems, policies, and beliefs (that negatively impact everyone who is not a young, white, Anglo-Saxon, able-bodied, heterosexual man), somatics and other social sciences teaches us that oppression is alive in our bodies and live in the very muscular make up of it.

Triggers awaken our survival strategies.

Oppression is a trigger.

Constant oppression is a constant trigger.

Therefore constant oppression creates a constant state of survival.

On an individual level, oppression can force one to be in a constant state of trigger and thereby in a constant state of survival. Habitual patterns of being are intrinsically shaped by experiencing life from a perpetual state of survival that inherently define the quality of life, one’s orientation to the world, and personal and professional relationships. Essentially, one’s personal resources, or leadership, is centered around and grounded in our conscious and unconscious patterns.

On a collective level, communities prone to feel the full brunt of the impacts of oppression, by design, will exhibit similar patterns from being in a collective state of survival. This collective state of survival can be seen in a plethora of social inaction such as voting as worthlessness, isolation, distrust and feelings of vulnerability are staples of constantly being in one’s own survival strategy.

And what happens when individuals and communities, constantly living under the boot of oppression, experience themselves and each other in a constant state of survival? We live our lives and our interactions are shaped by the live wire that our bodies are forced to remain in. That is, we are the person who is violently bumped into on the street only, every step we take has us being bumped and triggered along the path of our lives.

There are many antidotes and methodologies that support individuals and communities to reclaim their power and their lives that serve as a lifeline to undoing the deep patterns of constant survival mode. Social justice work across the globe does this work most brilliantly. Over the last decade or so, social justice movements, integrated with somatics and healing, works to address the individual and collective shaping that occurs from various forms of oppression.

Our experiences from being in a constant state of survival require each of us to do some inner work that materializes into outer impact. Otherwise, we are likely to perpetuate negative energy onto each other because we have not developed patterns to disrupt our shaping from oppression. The dis-ease of energy produced from oppression will literally live in our bodies until it is reactively released. When we do not or cannot make space to deal with the deep impact of oppression on our individual beings, we inevitably partake in a cyclical pattern of reactively expressing oppression, from the inside, to others around us.

This is vomiting rage.

It is our duty to know ourselves. It is our duty to truly understand who we are and how we came into our ways of being. It is our duty to know and regularly reflect on our ability to accurately align our values and principles with our actions. We owe it to ourselves first and then to one another.

Our individual change process is intertwined with our collective ability to change. This is how we create sustainable change in the world.